Autumn in Paris, Galerie Nathalie Obadia.

In Greek mythology, Marsyas was a satyr. He was a half-human, half-goat creature known for his skill in playing the aulos (double oboe), a wind instrument invented by Athena. One day, Apollo, celebrated for his unequalled talent for music, challenged Marsyas to a musical duel. The god of light, truth, music and arts was declared the winner by the muses and decided to punish Marsyas by tying him to a tree and flaying him alive. The myth of Marsyas has subsequently inspired numerous artists over the centuries. Fresh interpretations have emerged with each reading, reflecting on the theme of hubris and more broadly that of human existence.

‘Why do you tear me from myself?’ a tête-à-tête with Marsyas follows on in the tradition of exploring the sacrifice of this mythological figure. A series of six recent and hitherto unseen paintings attempts to capture the many facets of the satyr’s character. Joris Van de Moortel’s inspiration is drawn from the works of his predecessors, which he updates by sparingly integrating his own personal iconographic references. The artistic vocabulary of this contemporary artist rubs shoulders with that of painters from the Renaissance, in order to gain a better grasp of the complexities of today’s world. Joris Van de Moortel has often argued that the 16th century was at the root of major social and cultural changes that have gradually led to the alienation of humanity from its very nature. Over the intervening centuries, numerous interpretations of the myth of Marsyas have explored these broken links. This exhibition thus takes us on a journey through space and time, delving into the mysteries of our own existence.

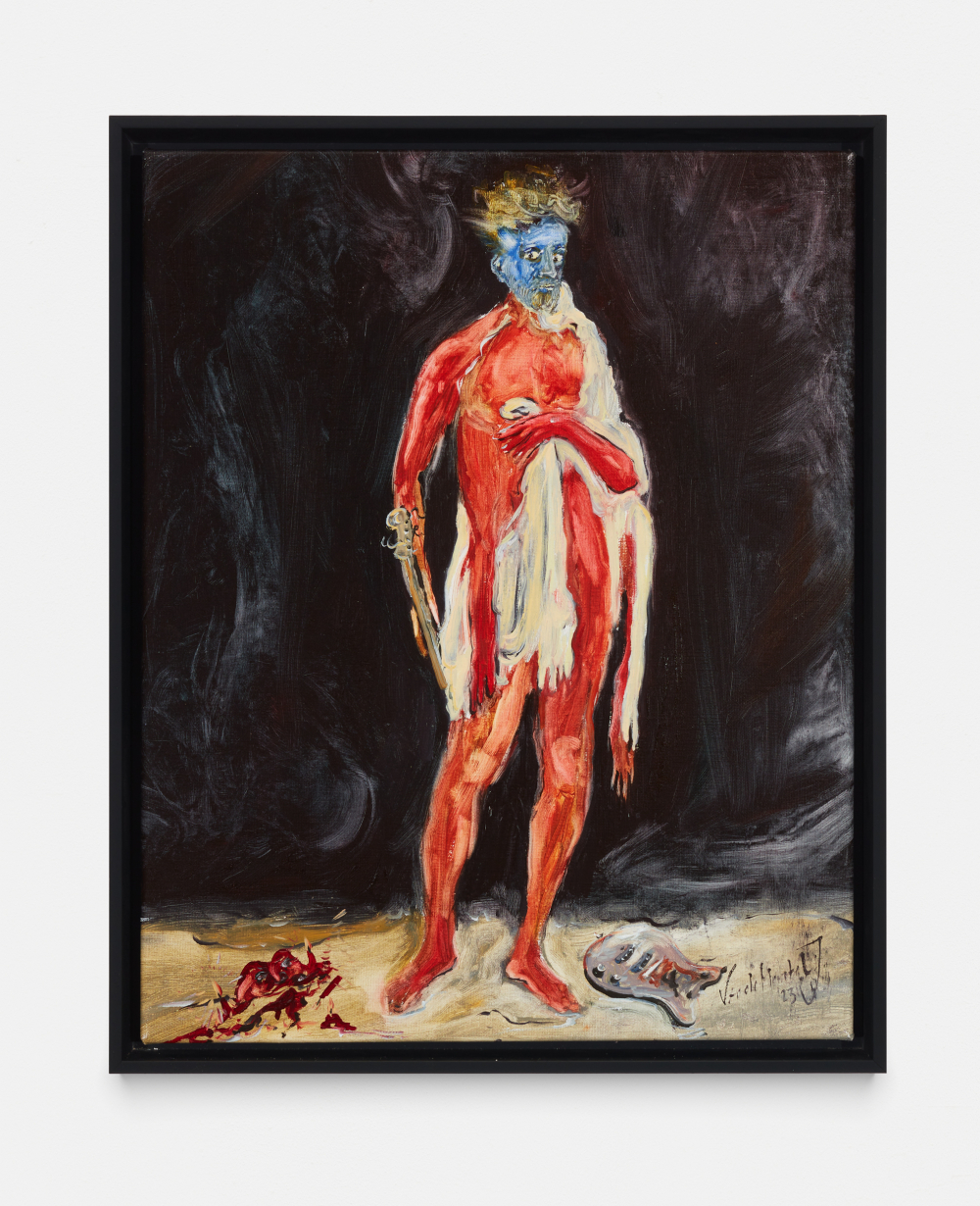

Each painting of the exhibition echoes a work inspired by the mythological story: versions by Michelangelo Anselmi (1492 - 1554), Titian (1490 - 1576) and Josep de Ribera (1591 - 1652) are among the chosen references. Joris Van de Moortel’s universe fits seamlessly with the selected works, a rich personal iconography running through his compositions, reflecting his unbridled creative vitality. As both a painter and self-taught musician, the multi-disciplinary artist Van de Moortel plays with details from the historical compositions and incorporates contemporary motifs such as an electric guitar or even his own face. In Flayed by a treble guitar string, a christian variation on a bloody theme – a reference to Matteo di Giovanni’s Saint Bartholomew the Apostle – the flaying knife is replaced by an electric guitar reduced to its component parts. The character depicted, draped in his own flabby skin and bearing the facial features of Joris Van de Moortel, stares out at the spectator. The figure is stripped of his physical envelope and appears to have mutilated himself with the very instrument that allows him to earn a living. The guitar motif also appears in the painting alluding to Michelangelo Anselmi’s Apollo and Marsyas, where the Viola da Braccio played by Apollo is replaced by an acoustic guitar inscribed with the words “this machine kills fascists”, in reference to the slogan used by the singer Woodie Guthrie in 1941.

These new paintings skilfully combine our collective history with Joris Van de Moortel’s personal experiences, as he represents himself in almost every composition. He depicts himself as both a satyr and a god, a martyr and a victor, these opposite points of view illustrating both sides of the same coin. This aspect allows the artist to emphasize his affinity with the two characters, who function like the two poles of a magnet: where everything is opposed, everything is also attracted; the nature of Being is in essence, both good and evil at the same time1.

In the myth of Marsyas, the satyr submits to the removal of his own skin: he sacrifices his outer shell to reveal his flesh, his inner self. The representation of the flayed body is, in this sense, a process of discovery: flesh reveals, it allows access to hidden secrets. This exploration of human existence is present throughout the exhibition space. The viewer will even observe Apollo slipping his hand inside Marsyas’ leg in vandal; mURysas, drawn in a more spiritual type of sacrifice – which echoes the painting Apollo and Marsyas by Jusepe de Ribera which will be exhibited at the Louvre from October. The medium of painting is a key element in Joris Van de Moortel’s quest: the thickness of the material deposited on the surface of the canvas transforms each composition into an almost visceral environment. The figures appearing in each painting are almost as if dissected, fragmented by the sharp, rhythmic brushstrokes.

By pronouncing Apollo as the victor, the myth of Marsyas highlights the triumph of celestial light over the earthly realms of shadow. This new series of paintings challenges these binary oppositions: the canvas mURsyas “le mât”, for example, depicts Marsyas and his tormentors on a ship, caught in a storm. In this situation, Apollo’s rational power seems incapable of saving the passengers in distress. Taking this myth as a springboard for reflection, the exhibition attempts to examine the ambiguity of the process of flaying: a brutal way of unveiling the insides of a being, either as a punishment or in order to make them the object of clinical study, revealing flesh that usually has its place in the realm of secrecy(2). The flaying of Marsyas, crossing the threshold that separates the epidermis from the viscera and thus the body from the mind, provides a perfect opportunity to further explore the human condition.

(1) DELEUZE Gilles, Spinoza, Philosophie pratique, Minuit, 1983, p. 45.

(2) DUMAS Stéphane, Les Peaux créatrices : Esthétique de la Sécrétion, Klincksieck, 2014.